By Chonon Bensho and Pedro Favaron

Chonon Bensho is an indigenous artist, of the Shipibo-Konibo people of Peru. She descends from the Onanya traditional medicinal wisdomkeepers and from the women that have preserved the artesanal and artistic traditions of their ancestors. She was raised, from childhood, in a traditional environment in her native tongue and was cured with the medicinal plants used by the people who strive to become masters of the kené designs. These designs express the philosophical and spiritual vision of the indigenous nations and attend to the search for beauty and balance. Kené art takes into account the profound relationship between human beings, ancestral territory, and the spiritual worlds.

Embroidery

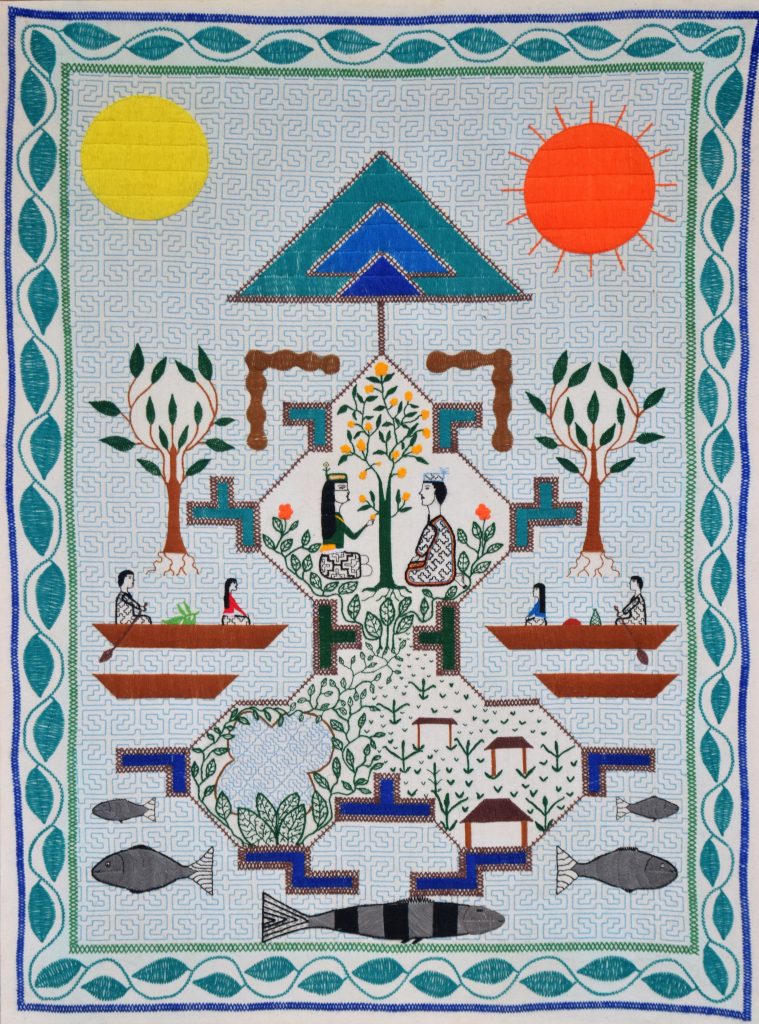

Maya Kené

Kené designs symbolize the identity of the Shipibo people. There are different kinds of kené. When the designs have been embroidered on cloth, as in this work, they are called kewé. In the center of this picture a Maya kené design, (one which is circular or goes forth turning), has been embroidered. The form is similar to the medicinal chants, the rao bewá (or ¨maya bainkin¨ as they are sometimes referred to in the poetic formula of chants) which, according to the Onanya healers, always advance turning around. The medicine circles round, and the healer is an instrument through which the curative force of the plants and the spiritual world materializes and is made effective. The circular design of the Maya kené also echoes the movement of the Amazon rivers with their prolonged meanderings.

The Maya kené in this picture is designed with a wide border, known as kano, a word that can be translated (with a certain poetic freedom) as ‘connection’: a principal path that ties together that which is diverse. In the ancestral architecture of the Shipibo people, the main frame, which centers and supports the house, is designated by the word ‘kano.’ In the case of this piece, the maya kené is what sustains the composition from the center. In the Indigenous conception, the center is the fountain of life and the root which permits equilibrium. Human beings could not live in a harmonious way that avoids excess if they did not know their own physical (yora), emotional (shina) and spiritual (kaya) center- if they ignored their place in the world. Equilibrium, according to the ancestral conceptions of the indigenous people, is born from the complement of opposite forces for this reason. Symmetry is achieved in this work through a kind of harmonious tension between complementary opposites (between man and woman, between the lake and the high land in which human beings live, between the horizontal movement of the fish and the vertical growth of the trees, between the sun and the moon).

At the same time, an ascending slant rises throughout the design. It goes from the world of water (jene nate) and passes through our world (non nete), until it reaches the superior world (nai nete)- the world of the heavens. The sky, too, is where the dialogue between the moon and the sun takes place. Between them, it has been decided that three equilateral triangles be placed, suggesting a vertical visual route. This ascending shift corresponds to the ancient teachings which say that humans only become full and realized beings when they are able to be a bridge between heaven and earth, as occurs with the Onanya healers who promote the link of the visible with the invisible, between that which can be perceived by the senses, and that which is beyond the senses. It is evident, as well, that the three triangles resemble the Christian symbolism of the Trinity The Trinity is meant to bring us closer to the unspoken presence of God and of the Great Spirit: that invisible and transcendent center that animates visible existence. For Chonon, there is no contradiction in liberally combining designs inspired by ancient Shipibos and Christian symbology. Unlike modern academic thought which pursues exclusive cataloguing, Indigenous thought is inclusive, and able to incorporate distinct elements without feeling threatened or contradictory. This view stems from an Indigenous Christianity, one which respects life and the plants and the invisible Chaikabonibo beings, who are like our angels and teach us all wisdom.

The principal design is surrounded by minor designs, beshe kené. These designs are placed on the edge or foot of the main design. This edge or foot is known in Shipibo by the name tae. Beshe kené are not mere adornments. In addition to their decorative function, they convey an ancestral aesthetic pattern that comprehends the truth that all of existence has a vibration and a spiritual knowledge that is expressed in the kené as the symbol of the spirituality of beings.

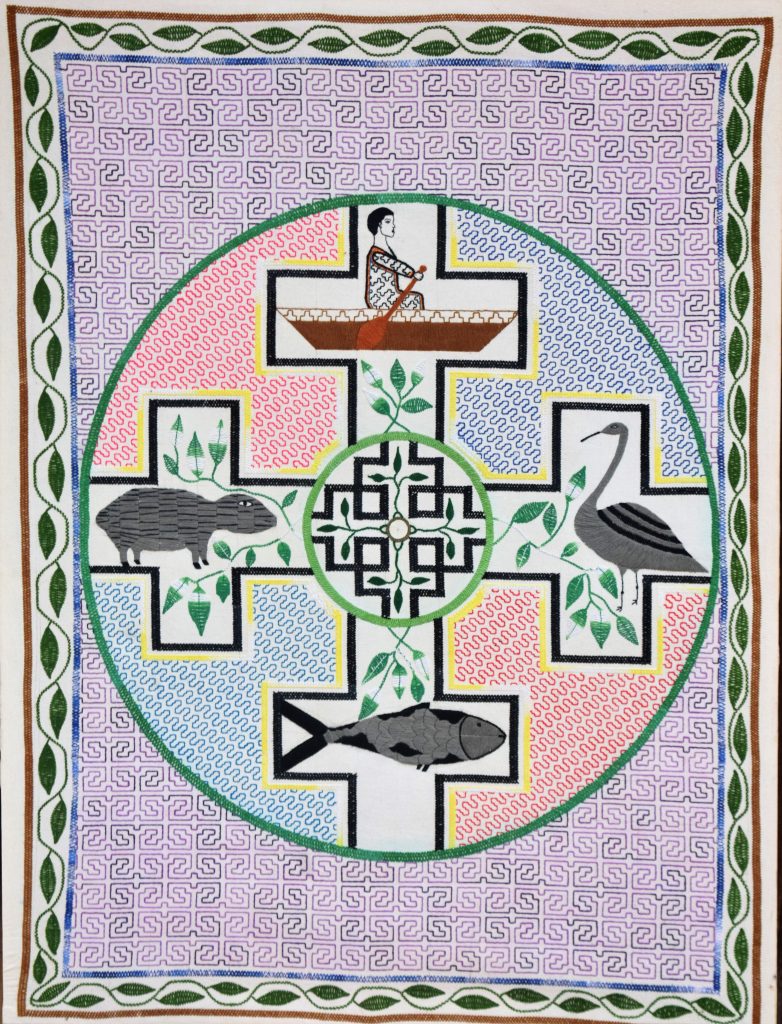

Koros Kené

Although the word ‘koros’ seems to be a neologism, or a recently coined phrase in the Shipibo language that stems from the Castilian word cross; this kené symbol in the form of a cross greatly precedes the arrival of Westerners to the Amazon territory. Koros seems to be nearer to the symbol of the chakana (staggered cross), which has been present in distinct Indigenous cultures spanning from Patagonia to north of the Andes and further since an undetermined time. The most common of kené koros were associated with the festival of Ani Xeatil, a traditional celebration that occurred, in most cases, when an adolescent was getting ready to marry and be circumcised. Relatives from afar were received with an abundance of food and drink. The Shibibo cross was placed in the center of the esplanade in which the main celebration occurred. Animals from the countryside, which had been trapped alive, were tied for those attending the celebration to shoot with bows and arrows during the event. Later these animals were eaten in a communal form, reinforcing the ties that united the relatives.

The symbology of the the cross as center, as the meeting point, allows us to understand the symbol as a place of resolution of conflict and complementarity. Meetings among difference could be at times friendly and festive. At others, conflict arose, such as during the feast of Ani Xeatl when two men decided to fight. The men did not try to destroy one another. The conflict was resolved when one of the men wounded the other so that all past offenses were forgotten, and peace and cordiality was reinstated between them. It was all about recuperating balance, a harmonious and healthy coexistence, so that internal conflicts did not completely destroy the ties of family relation, and being together would be possible and happy.

From a horizontal and geographical reading, the center of the cross seems to mark the point of convergence for the town, for the family members, non kaybobo, who came from every corner of the region, from the four sacred directions and cardinal points, to visit the place where the Ani Xeatl was held. Conversely, from a vertical reading, the cross seems to point to the complement of right and left, of high and low. Like the majority of kené designs, the kené koros seems to symbolize the ancient teaching regarding the need for us to complement one another and live in equilibrium: our two eyes complement one another, our two hands complement one another, man and woman complement one another, our world complements the world of the spirits.

In the specific case of this work, a cross is proposed as a symbol of the complementarity that should exist between human beings and the rest of the living beings in the territory. For this reason, the background of the kené symbolizes the fish and inhabitants of the world of water, jene nete. On the left side of the cross is painted a ronsoco, one of the animals from the countryside that belongs to the four-footed beings that walk in the countryside and whose meat has been part of the regular diet of the Amazonian people. In the top of the cross a man appears navigating in his canoe, which allows him to enter into contact with the different worlds of our ancestral territory. The whole of this koros design is a symbol of the inseparable ties which connect all living beings and between those that should always exist in a state of balance. The ancient teaching is contrary to the practice of the modern world which does not respect the life of the rest of beings and thinks that they can extract anything they desire from the land. The codex say that capitalist modernity breaks with the healthy equilibrium with the land which the elders knew how to maintain.

nane

The fruit of the huito plant(Genipa Americana) is called nane in the Shipibo language. It is an important plant for Indigenous ethnobotany. The boiled juice of this fruit produces a dark blue dye when it comes into contact with the skin and the atmosphere. Women and men used to make designs on their faces with this dye to attend celebrations. These designs provided an account of cultural identity and belonging for the Shipibo people; in other words, huito was a foundational fruit in the symbolic construction of identity. In the past, some people covered their entire body with huito to avoid sunburn, and currently it is still used by men and women to dye their hair. The artwork above explains the importance of huito for the Shipibo-Konibo people by placing it in the center of the image. An embroidered work has been carried out in which the traditional kené (geometric designs) coincide with figurative elements of modern art, thus achieving a harmonious and balanced encounter between the ancestral and the modern.

Oil paintings

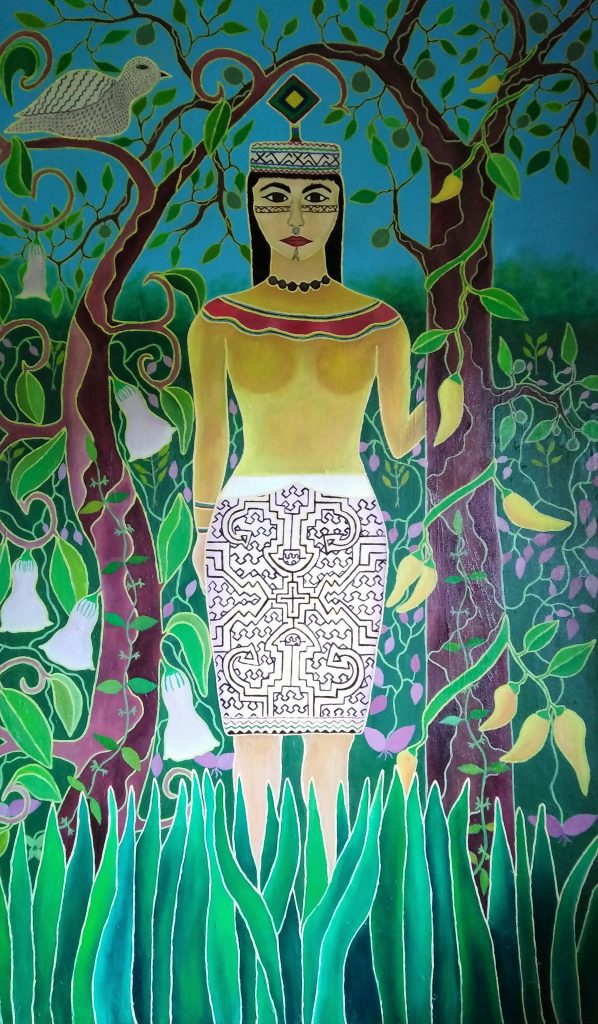

Jene ainbo

Our grandparents told us that at the beginning of time, when the world was new, the old Shipibo dressed poorly. Their clothes had nothing special, no beauty, no joy. This was true until one day when a woman found a mermaid at the shore of a lake. That mermaid was a beautiful young woman who had her whole body covered with kené designs. The woman returned to her house and drew the designs she had contemplated onthe mermaid’s body on the ground. Since that time, the Shipibo have embroidered those designs on their clothes, painted them on fabrics and ceramics, carved them in the wooden beams of their houses and in the oars of their canoes. For our grandparents, the kené design was not a human invention, but a gift from the invisible beings from the water world (jene nete); they who live at the bottom of lakes and rivers in our ancestral territory. In the artwork above, the mermaid that gave birth to the kené has been painted to teach that water is not only a life source for human beings, for plants that bring healing and wisdom, for fish and fishing birds (like the different herons that are part of the image). Water is also for the invisible beings who are the legitimate owners of that world. Human beings cannot live well without clean water and we cannot devour water resources as if we were the only owners, because the true owners of the waterworld are extraordinary beings, of great thought and knowledge, to whom we owe the kené, those unequivocal symbols of our cultural identity which we inherited from our ancestors and our spiritual strength. The human being who comes to see these beings from the water world and establishes a relationship with them, receives his strength and knowledge and becomes a doctor and wise Onanya.

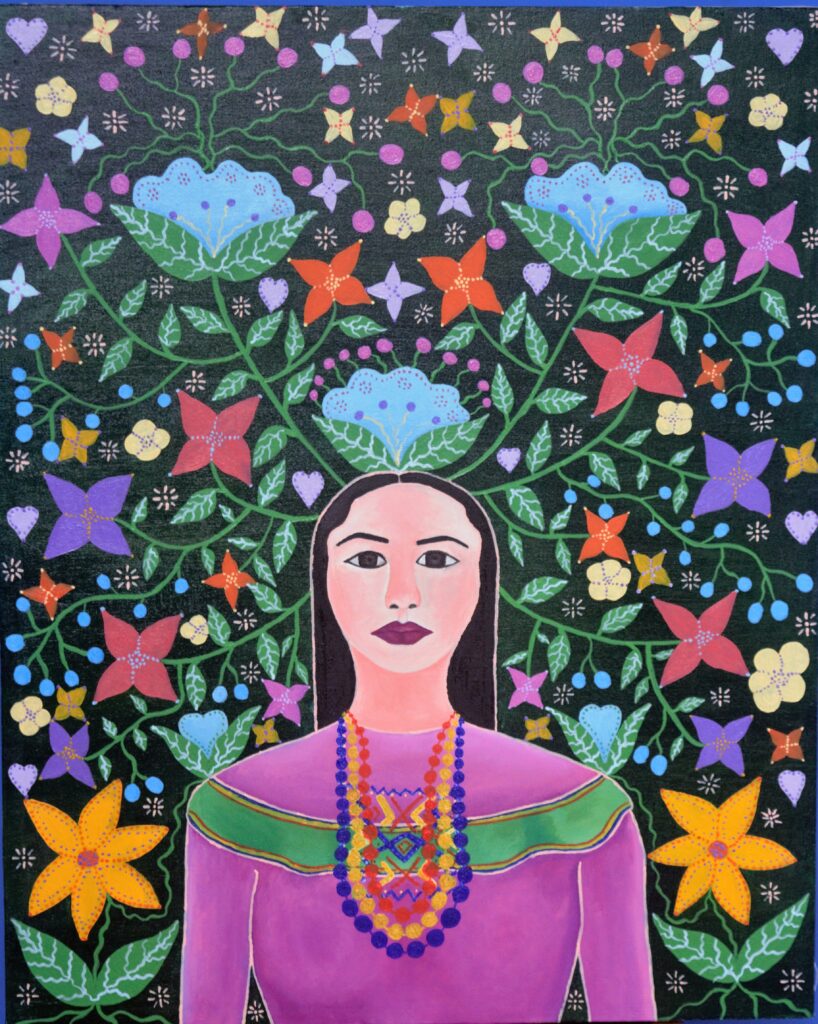

Kené Rao Numa

The different medicinal plants, known since ancestral times by the ethnobotany of the Shipibo-Konibo people, are called rao in the Shipibo language. The plants that could be classified under the name of kené rao are those used to learn how to make kené designs and become skilled artists. In the painting above, three different types of kené rao have been represented. 1) in the lower part of the image appears the kené-waste plant, a plant similar to fully grown grass, whose root is scraped with water to produce a liquid to be used as eye drops. 2) Likewise, in the middle part of the image, with the shape of a rope (nishi) with leaves, the plant ipon bekené has been painted. The chlorophyll from this vine is extracted and used as eye drops as well. 3) The third plant represented in the painting, similar to a croton plant, is called kené samban. It is used to brew steam baths for the hands. In these last two types of kené rao, the leaves have beautiful designs similar to the kené, which is an indication of the medicinal wisdom they keep. People who diet upon these plants, when using them, dream of old women and men who show them beautiful kené designs.

According to the spiritual knowledge and vegetable metaphysics of the Shipibo-Konibo people, the different Rao plants have Spiritual Keepers who manage them, known in Shipibo as Rao ibo. Although these extraordinary beings are not usually visible to human beings in an ordinary state of consciousness, they manifest themselves in the dreams of the person who fasts and in the visions produced by the intake of ayawaska which allows human beings to learn from them and receive their strength and wisdom. In this case, the owner of the rao plants has been painted as an old but young woman, of a beauty that seems timeless. Although in the daily Shipibo language woman is known as ainbo, this painting is titled Numa, meaning dove, because this is the metaphorical form by which the poetic songs of the ancient Shipibo call women. The keeper of the kené has white skin because she lives in the humid areas of the forest and the sun never directly hits her body. She has a beautiful Mayti crown, seed necklaces and a pectoral, a cotton blouse and a chitonti panpanilla. She also has a temporary tattoo with kené designs on her cheeks, painted with the dye of the huito fruit. She is between two trees. The white toé tree, with its beautiful bell-shape flowers, is a medicine of great wisdom, and has been painted to indicate the relationship of the kené with the medicinal and visionary world. The huito tree, whose fruit produces a black dye in contact with the atmosphere, has been used in Amazonian art since ancestral times.

Samatai jonin nama

For the Shipibo-Konibo people, as for other indigenous peoples from the Americas, the soul (kaya) is liberated during dreams from the limits of the physical body (yora), and can access other spiritual worlds where it talks with extraordinary beings and obtains all sorts of knowledge. Although all humans dream, the Onanya healers are those who dream with more frequency, intensity and clarity. Those dreams are not normal; they are revelations from the spirit worlds. Because of their initiation rites, the Onanya can travel in these worlds with greater skill and obtain in them irreplaceable wisdom. During their initiation, the Onanya learn to move in the spirit world where they get their wisdom and power; these learning processes are called “dieta” in the regional Spanish, and “sama” in the Shipibo language. In this piece, a sleeping dietador or initiate has been painted, dressed in a traditional cushma tunic (tari) with beautiful I kené designs. The tunic is not just any garment. Interpreted poetically, it symbolizes the spiritual knowledge and protection of the dietador. The dietador sleeps surrounded by various medicinal plants and trees, which are part of the ‘dieta’ and through which he gains his medicinal powers and songs. In the dream he appears together with yana puma, known in Shipibo as wiso ino, who is a spiritual guardian that will defend him from any attacks of bad intention or brujeria.

Rao Nete

Rao nete is a Shipibo expression that means medicine world. This medicine world is a spiritual dimension with which the Onanya healer enters into contact in order to heal. It is a subtle and luminous world of a high spiritual vibration, from which the healing force of medicinal songs and the healer’s whistle emanates. The Keepers of the Spiritual World are known as Chaikonibo; they are our ancestors who live far from the city, in purity, conserving the ancient wisdom. They are compassionate beings who offer health to those who ask with humility. This painting shows the trinity of the connection between the patient’s soul, the Onanya healer’s soul, and the spiritual owner of the medicine world.

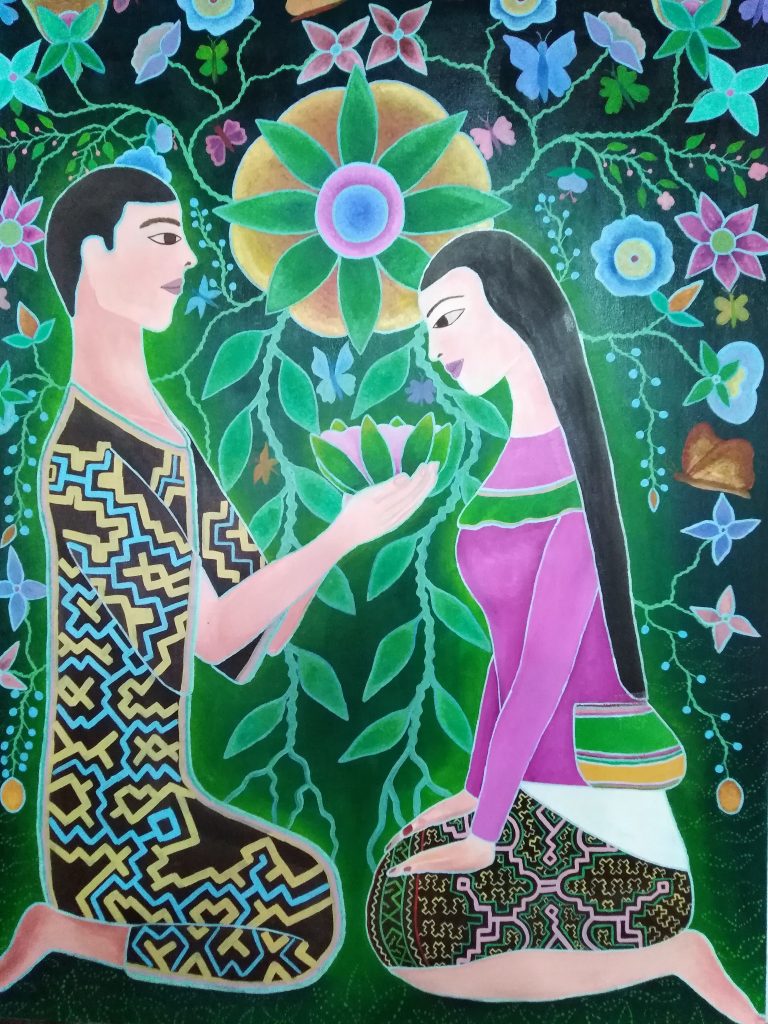

inin nete

Inin nete means aromatic world, and is one of the fundamental aspects of the traditional medicine of the Shipibo-Konibo people. The inin nete represents a perfumed force that arises from the spiritual medicine world, and is the foundation for healing the patients. The Spiritual Keepers of the medicine are always aromatic beings that emanate a smell like flowers and perfumed plants. To reach this spirit world, the Onanya healer must bath with the leaves of the noirao plant, which are aromatic leaves that change the smell of the human being, purifying him and making him smell like plants. The aromatic world purifies all of the patient’s impurities and bad energies. When the Onanya reaches this world of high vibration and indescribable beauty, he learns the feminine aspects of the medicine and marries the perfumed beings of the spirit world. In this way, the healer is transformed into a being like the Spirit Keepers of the plants, and becomes part of their spiritual community.