By Juan G. Sánchez Martínez

Translated by Catherine Thompson

Achu Kantule (Osvaldo De León) was born in 1964 in Ustupu, the Gunadule Nation (Panamá). He began to paint, as a self-taught artist, in the ‘80s. In 1996 he won the National Prize for Painting from the Cultural Institute of Panamá. In 2001, he graduated from the University of Panamá with honors (Sigma Landa), obtaining A Bachelor’s Degree in Plastic and Visual Arts. He has had over 24 individual exhibits throughout the Americas and Europe, and has participated in various joint exhibits. In 2004, he received a prestigious scholarship from the National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian Institution).

Recently, we met at II Congreso SoLEI, at the University of Magdalena (Santa Marta, Colombia), where Achu was invited as a special guest. Here he explained to us, the assistants, some of the principles of traditional Gunadule art: duality (“Even in celebrations we drink two shots, to honor both man and woman” he said, while laughing), repetition, abstraction, and multidimensionality (“because we believe that the world consists of eight dimensions”). We learned that there is a realm of the arts in Gunadule cosmology, in which the Gods dreamed the designs and textiles of the molas and then came to teach the women of the community.

Watch the talk on Youtube

According to Achu (meaning ‘little tiger cat’ in Gunadule), the multidimensionality of the molas and their paintings correspond to the four languages that the community uses: 1) the language for daily use, 2) the language sung by spiritual leaders, 3) the ritual language of the initiated, which is to say, the curative songs that are written in pictograms, and 4) the spiritual language, that is only thought, not spoken. In effect, these paintings that Achu has shared with Siwar Mayu engage with multidimensionality: different levels of language are traversed by different depths of meaning: “My work has to serve a purpose, which may be to heal. Art is therapy”. His first critics, however, wanted Achu to paint portraits, “but realism, like religion, is something that was imposed,” he pointed out.

Duality, repetition, abstraction, multidimensionality can be found in the work of Achu, and to better understand this, he explains it through the molas, “historical documents.” The molas are like an “ambulant book”, because the women carry the history of their community in their clothing.

Check out the collection of molas at the Smithsonian.

While sharing an image of a mola with three rows of yellow forks, in front of blue, orange and fuschia backgrounds, which ultimately turn into strange objects, Achu explained that traditional Gunadule art preceded western optical art and pop art styles. A mola in which four telephones are ringing (vintage rotary dial phones) served to demonstrate how overlap creates textures, and like a woven fabric, they can create the sense of movement, vibration and ringing!

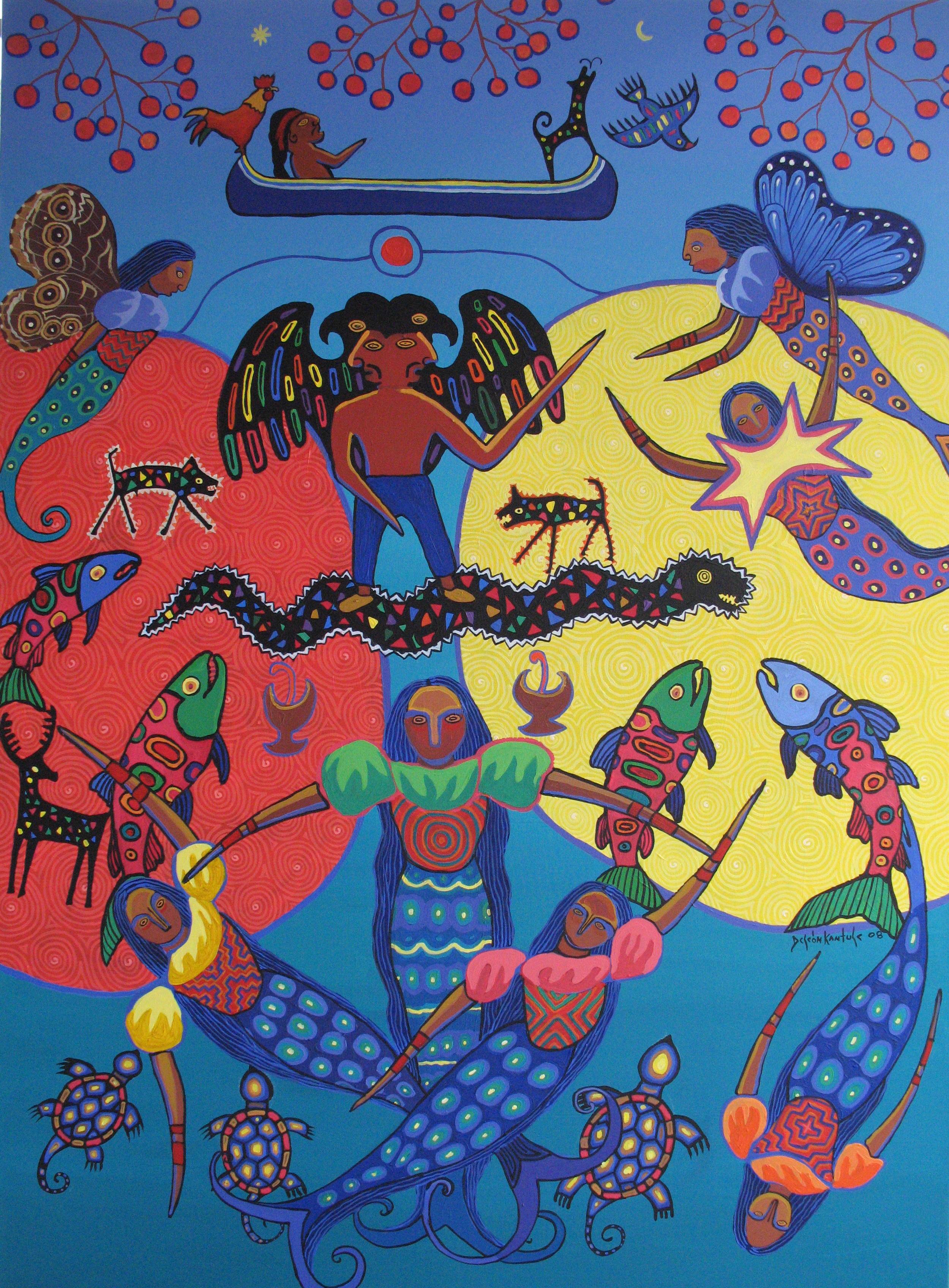

Achu also explained that the animals that inhabit the Gunadule molas and his own paintings are echoed in the cosmology of his community: the crocodile transports sick spirits because it is an amphibious being, and there are certain sharks that are allies of people fighting those same spirits. The jaguar is also very important in this iconography, because it “represents power and strength”. There are sacred mountains, kalus, where only innocent children and psychics, the Neles sages, can go. “For each animal, the snake, the jaguar, the eagle, there is a sacred place” in the land, said Achu, while indicating a book that can be found in the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg.

View the Guna collection in the William Benton Museum of Art (Connecticut)

Achu is a storyteller and always takes any opportunity to remind the audience or his friends, of the strategies used by his great-grandfather, Nele Kantule, to win the Guna Revolution. The story goes as follows: the revolution began in Panamá in 1925. Through the construction of the canal, the Panamanian Government opted for a policy of “civilization of the savage tribes”. They sent policemen obligating the community to abstain from practicing their medicine. “The mola was prohibited, which is why I call the mola, the art of resistance, because from there the Guna people arose. My great-grandfather was the leader, Nele Kantule,” narrated Achu.

The history of the revolution in Achu’s account tells that before attacking the police who were sent by the Panamanian Government, the great Nele Kantule, decided to send eight suitcases filled with Guna artifacts (books, writings, molas, and sculptures) with two young emissaries, one to Europe, and the other to the United States. Achu continues: “he said, “when we finish with our enemies, the world will say we are savages, but we are not savages because we have our literature, we have our art, we have everything””. As the sage Sequoyah implementing the Cherokee syllabary, the sage Nele Kantule assured that the world found out about the ancient, cultural richness of the Guna Yala.

At the end of his talk, Achu gifted us with another story, about Iguanigdipipi, a young man who became a Nele by the age of 25- teacher, musician, and one of the first contemporary Gunadule artists. His map of the ancestral territory, with notes that explain the reasons behind the revolution, was painted in Canada in 1924 (where Achu now lives part of the time). Achu worked on this map during his investigation at the Smithsonian in 2004. His grandfather was the official translator of Iguanigdipipi. Achu told of a scene, in that very map, in which a missionary arrives and speaks with a bird from Guna cosmology, siku the interpreter. “We call people that speak various languages sikui,” he explained. Yes, the art that Achu has shared with this river of hummingbirds (Siwar Mayu) is inhabited by sikui. Siwar Mayu is a multilingual river!

At the end of his talk, while presenting a Pre-Columbian vessel, Achu pointed out: “Scholars want to separate us, don’t they? The say Pre-Columbian time is different than the present. But we still have the same connection. I do not know what the purpose of separating is.” Achu’s work is the proof of a continual resistance, from the mola to installations and conceptual art. The 300 islands of Guna Yala are being affected by the accelerated rising sea level, in addition to plastics and the contamination which tourism leaves behind. The work of Achu Kantule is a multidimensional response to a current urgency, not only of his community but of this “pale blue dot.”

Check out Achu’s work in Centro América Sumergida y Dupu (Isla), la casa de los Gunas que se hunde en la Bienal Centroamericana (2016)

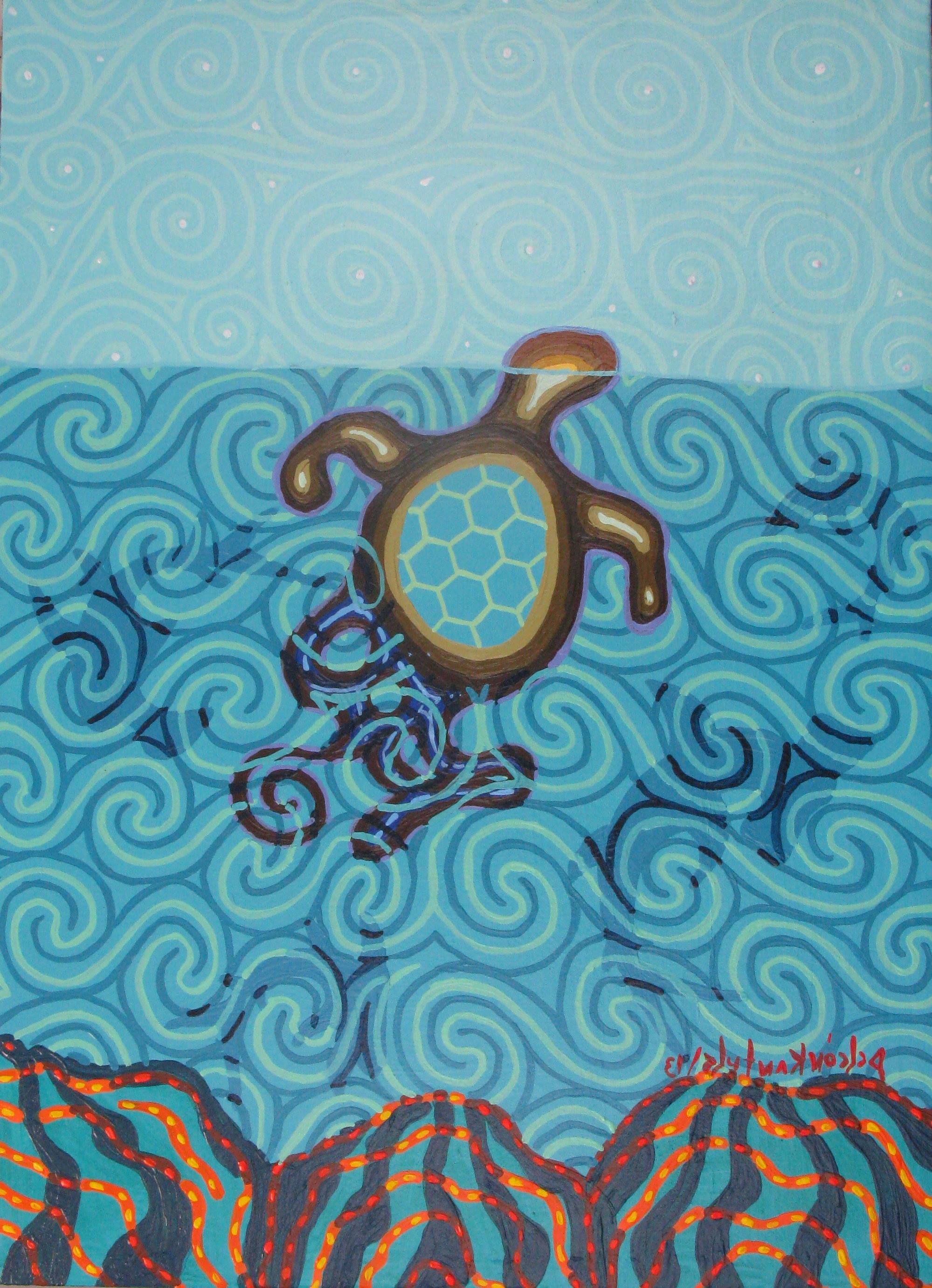

As observers of this work we look at the different layers of one same tapestry. Acrylic on canvas. From a canoe we submerge ourselves in geometric shapes that undulate in the water (spirals, crosses, rhombuses) which take us to a new depth, one of confronting crocodiles and sharks, Neles that transform, and grandmothers dressed in their molas protected by turtles who rescue life from the abyss. Behind warm colors and the visual vibration which the multiple layers create, the work of Achu deals also with a cosmic battle in which the grandson of Nele Kantule continues the revolution, for life, water and the ancestors of Guna Yala.